miércoles, marzo 28, 2018

lunes, marzo 19, 2018

jueves, marzo 15, 2018

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird

I

Among twenty snowy mountains,

The only moving thing

Was the eye of the blackbird.

II

I was of three minds,

Like a tree

In which there are three blackbirds.

III

The blackbird whirled in the autumn winds.

It was a small part of the pantomime.

IV

A man and a woman

Are one.

A man and a woman and a blackbird

Are one.

V

I do not know which to prefer,

The beauty of inflections

Or the beauty of innuendoes,

The blackbird whistling

Or just after.

VI

Icicles filled the long window

With barbaric glass.

The shadow of the blackbird

Crossed it, to and fro.

The mood

Traced in the shadow

An indecipherable cause.

VII

O thin men of Haddam,

Why do you imagine golden birds?

Do you not see how the blackbird

Walks around the feet

Of the women about you?

VIII

I know noble accents

And lucid, inescapable rhythms;

But I know, too,

That the blackbird is involved

In what I know.

IX

When the blackbird flew out of sight,

It marked the edge

Of one of many circles.

X

At the sight of blackbirds

Flying in a green light,

Even the bawds of euphony

Would cry out sharply.

XI

He rode over Connecticut

In a glass coach.

Once, a fear pierced him,

In that he mistook

The shadow of his equipage

For blackbirds.

XII

The river is moving.

The blackbird must be flying.

XIII

It was evening all afternoon.

It was snowing

And it was going to snow.

The blackbird sat

In the cedar-limbs.

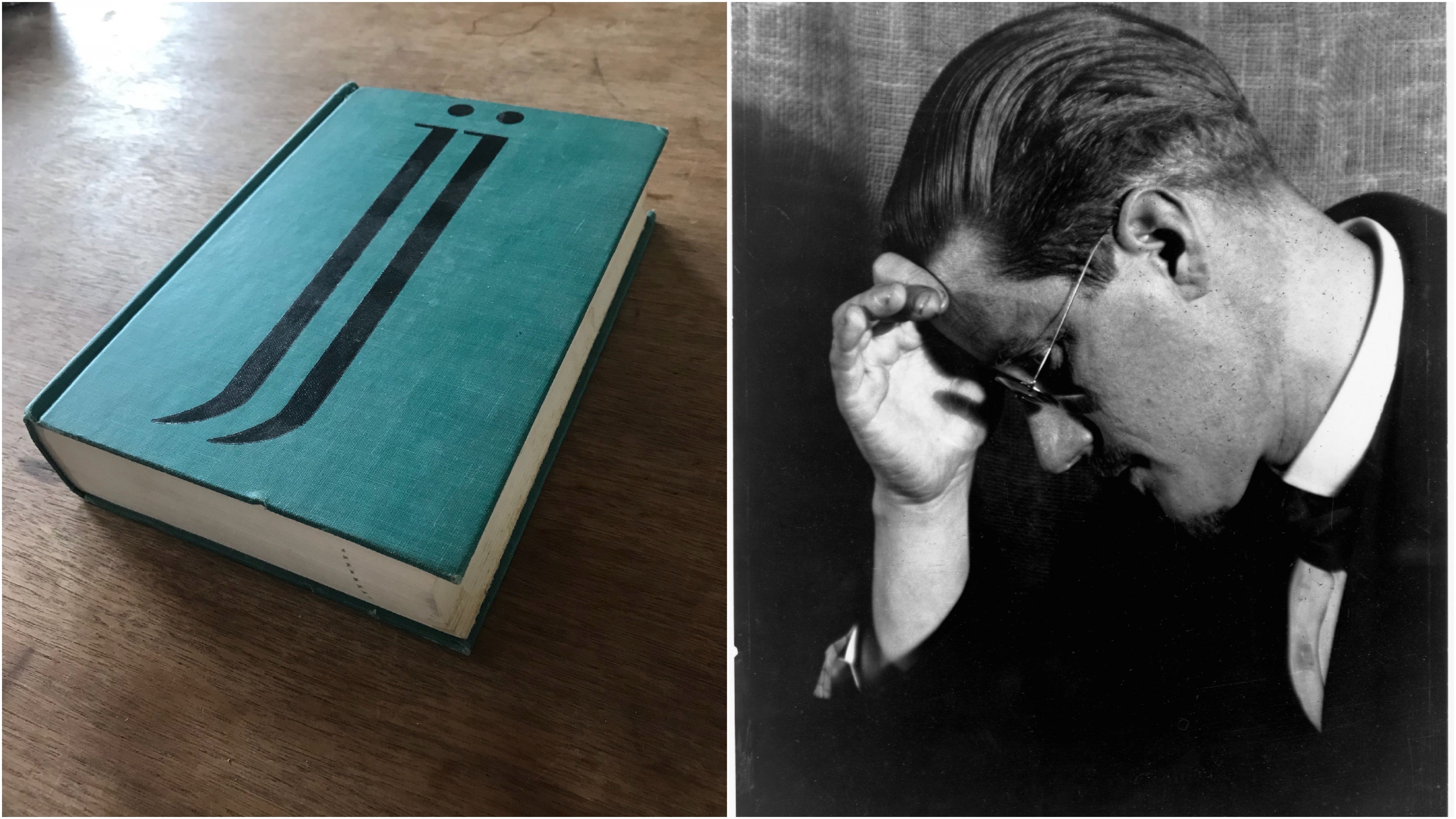

Ahora que estamos en Finnegans, Ulises nos parece fácil.

This month marks the 100th anniversary of the first

appearance of James Joyce’s Ulysses,

originally serialized in The Little

Review between March 1918 and December 1920, and then

published in its entirety in February 1922. From the start, it was held in almost

religiously high regard, but also as a work of imposing

impenetrability and pretension. Vladimir Nabokov called it “divine”; Ernest

Hemingway called it “goddamn wonderful.” Virginia Woolf called it “illiterate,

underbred”; Aldous Huxley called it “one of the dullest books ever written.”

While literary giants debated its merits for decades, many readers merely

shrunk away entirely, despite the novel’s enduring reputation as one of the

20th century’s defining English-language masterpieces. Its status as an

impenetrable masterwork is self-reinforcing at this point: It is as great as it

is complex, an Everest to be scaled only by those hardy enough to undertake it.

I used to have a habit of leafing through the huge-ass

novel at bookstores, seeing a weird soup of words and non-words commingling,

and wondering what advanced degree of intellectual capacity I’d need to unlock

in order to not just slog through the book but really grok it, get the whole

thing, perhaps casually reference it at future dinner parties. (I would also be

a regular attendee of dinner parties in this genius future.) Standing in one of

those old-timey Barnes & Nobles, I’d flip to the front, see that opening

buckshot of words—“Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead”—and

return to the cozier confines of other reading, the sort of books that didn’t

necessitate a separate guidebook to understand. This went on for years until,

for whatever reason, I ended up finally acquiring a copy in my first year out

of college, and decided to give the whole thing a go, at which point I

discovered something truly shocking.

Ulysses is

not that big of a fucking deal. Yes, it is complex; yes, it is great. But you

could totally read it, and you should.

A lot of modernist literature plays aggressively with

the canon of Western literature, reconfiguring religious texts and classical

works with a sacreligious glee. Ulysses is

no different: From its title onward, it chops up Greek mythology, Catholic

guilt, Irish history, and the English language, playing them off of each other

with ever-increasing archness. You may know this already about the book, or by

only skimming its Wikipedia page. So the thinking might be that in order to

read Ulysses,

you’d need to read what Joyce had—you’d need to have some semblance of his

worldliness in order to engage in the 700-page dialog with him. You probably do

not have time to read the entire canon of Western literature, so I can

understand why this would be intimidating.

In reality, you really only need to read two books

before you read Ulysses,

and those are Joyce’s two books before Ulysses. The short story collection Dubliners, if you weren’t

forced to read it in high school, is a series of brief vignettes of

turn-of-the-century malaise; it’s heartbreaking and beautiful, and a great

introduction to the themes of stasis that define his later works. It is also

written in strikingly clear, sturdy language—no Latin required. Follow that up

with his first novel, A Portrait Of

The Artist As A Young Man, published two years later, which

introduces Stephen Dedalus (an important character in Ulysses) as well as Joyce’s

stream-of-consciousness prose style. This galloping, lyrical style can seem

intimidating if you jump in midstream, but in the Portrait it scales from the meandering

thoughts of a child in the earliest chapters to the more densely introspective

preoccupations of an adolescent. It rises in complexity as it goes, letting you

keep up alongside it, and a lot of its innovations are pretty well-worn stuff

over decades of imitation. If you’ve read Dubliners, you can read Portrait.

And if you’ve already read those books, then guess

what? You’re ready for Ulysses,

my friend. You will, of course, want some sort of guide along the way. I used Stuart

Gilbert’s study, which was sort of the first to crack the book’s

code, but there are plenty others out there. All of them will, in one way or

another, break down the book’s structure, which is part of what makes it easier

to read than you’d think. Ulysses is

broken up into 18 chapters, each of which varies wildly from all of the others,

and those chapters themselves comprise three parts. So at any given time,

you’re not tackling Ulysses,

The Greatest And Most Complex Book Ever—you’re reading the colossal drama of

“Cyclops,” or you’re reading the filmic vignettes of “Wandering Rocks,” or

you’re reading “Sirens,” the chapter in which Joyce tries to come up with words

that sound like

music feels,

which is as batshit insane as it sounds. These chapters and sections are

discrete challenges that all have a specific

set of allusions and techniques and motifs, but once you know

them, they’re wildly inventive, fun little challenges to undertake, and then

they’re over. If you were feeling ambitious, you could read a chapter in a

sitting or two. You could even knock out a few chapters over a few weeks, then

take a break and come back; you will not forget what’s going on. The plot

mostly consists of a dude walking around, thinking about things, and

occasionally cranking his hog.

This brings me to my last point, which is that, once

you’re in, the book is filthy, and very funny. Occasionally Joyce’s sexually

charged letters to his wife make the rounds; if you

like those, you will love Ulysses,

which reaches its first of several climaxes during a hallucinatory chapter set

in a brothel. Joyce’s vaunted stylistic extravagance was innovated, in part, to

conjure the density of human thought, and he didn’t shy away from how often

those thoughts drift toward the needs of the flesh. The book is full of piss

and shit, low-brow puns, hunger pangs, and endless horniness; what’s so fun

about the book is watching him describe all of this in some of the most heavenly

sentences ever constructed, and fitting it into the larger tapestry of Western

intellectual culture.

It took me the better part of a year to read it, but I

read at a snail’s pace for some probably undiagnosed reason; a faster reader

could knock the whole thing out in a few months, easy. And then, guess what?

You’re in the fucking club! Having read Ulysses is almost as fun as reading Ulysses, and not just because

you’ll have a dog-eared and underlined copy as proof of your intellectual

magnificence. I still flip through the book longingly today, just as I did

before I had read it, revisiting spaces and ideas and jokes and confluences of

words that don’t exist elsewhere in fiction. When you’ve engaged that deeply

with a book, your affection for it and its characters is enduring: You want to

revisit old affable Leopold, or proto-sadboy Stephen, or Molly, who looms large

over the novel and (spoiler?) speaks at last in the book’s oceanic final

chapter. The book, which attempts against all odds to pack the fullness of

Western literature and Irish history and human emotion into a single man’s

meandering day in Dublin, is an overwhelming affirmation of the possibilities

of life, which is part of what makes Molly’s final “yes” such a perfect ending.

It may take you a year to read it, but in the end it kicks you in the ass, out

in the world, demanding you live fully and chase beauty wherever it rears its

unlikely head.

Ulysses, in

other words, is a justification of the effort it takes to read Ulysses. Hence the overwhelming

cult around it. Go wandering into its labyrinth and you come out changed by the

effort. But—and this is my point—you will find your way out, and you’ll be

changed, in some measure, by the experience, too.

lunes, marzo 12, 2018

Joyce and Budgen

Joyce and Budgen spent much of the war in the same city, Zurich, and similar social circles of artists,[6] writers and musicians. According to Budgen's 1934 memoir James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses, Joyce regularly discussed aesthetic matters with him, often referring to the content of Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. The last of these three, Budgen stated, Joyce referred to at the time as Work in Progress; indeed a number of the conversations he reports as having had with Joyce imply that the author was working out the form and content of this work in part by arguing with Budgen.

Joyce scholar Clive Hart wrote about him:

Frank and Francine Budgen are buried at the graveyard of St George’s Church, Crowhurst, Surrey.