Un regalo de JFV

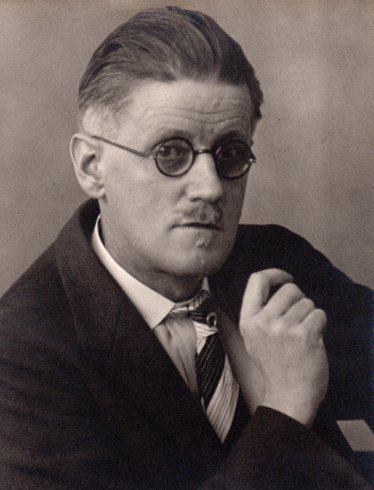

James Joyce’s Humorous Morphology of the Many Outrageous Myths about Him

by Maria Popova

How the celebrated author earned a reputation as a lazy coke-head movie mogul with a peculiar clock habit.

While inhabiting all our contradictory selvesmay be the key to true happiness, when it comes to those in the public eye, such manufactured and often conflicting mythologies of self are often projected onto them by way of popular legend. This is especially true of those most reclusive and reticent about offering direct glimpses of the private persona beneath the public figure, thus enveloping the observed in alluring ambiguity which the observers readily fill with fanciful hypotheses and contemporary folklore.

While inhabiting all our contradictory selvesmay be the key to true happiness, when it comes to those in the public eye, such manufactured and often conflicting mythologies of self are often projected onto them by way of popular legend. This is especially true of those most reclusive and reticent about offering direct glimpses of the private persona beneath the public figure, thus enveloping the observed in alluring ambiguity which the observers readily fill with fanciful hypotheses and contemporary folklore.

From the ceaselessly entertaining Funny Letters from Famous People (public library) — which also gave us the best resignation letter ever written, courtesy of Sherwood Anderson, and Lewis Carroll’s hilarious letter of apology for standing a friend up— comes this letter James Joyce wrote to Harriet Shaw Weaver on June 24, 1921, mere months before Ulysses was published by Sylvia Beach. The celebrated author lays out a characteristically long-winded and uncharacteristically humorous morphology of the outrageous myths and legends about him, while managing to slip in a dual jab at psychiatry frenemiesJung and Freud — an aside especially gratifying in its symmetry, given how meticulously Freud engineered his own myth.

A nice collection could be made of legends about me. Here are some. My family in Dublin believe that I enriched myself in Switzerland during the war by espionage work for one or both combatants. Triestines, seeing me emerge from my relative’s house occupied by my furniture for about twenty minutes every day and walk to the same point, the G.P.O., and back (I was writing Nausikaa and The Oxen of the Sun [for Ulysses] in a dreadful atmosphere) circulated the rumour, now firmly believed, that I am a cocaine victim. The general rumour in Dublin was (till the prospectus of Ulysses stopped it) that I could write no more, had broken down, and was dying in New York. A man from Liverpool told me he had heard that I was the owner of several cinema theaters all over Switzerland. In America there appear to have been two versions: one that I was almost blind, emaciated and consumptive, the other that I am an austere mixture of the Dalai Lama and sir Rabindranath Tagore. Mr. Pound described me as a dour Aberdeen minister. Mr. [Wyndham] Lewis told me he was told I was a crazy fellow who always carried four watches and rarely spoke except to ask my neighbor what o’clock it was. Mr. Yeats seemed to have described me to Mr. Pound as a kind of Dick Swiveller. What the numerous (and useless) people to whom I have been introduced here think I don’t know. My habit of addressing people I have just met for the first time as “Monsieur” earned for me the reputation of a tout petit bourgeois while others consider what I intend for politeness as most offensive. . . . One woman here originated the rumour that I am extremely lazy and will never do or finish anything. (I calculate that I must have spent nearly 20,000 hours in writing Ulysses.) A batch of people in Zurich persuaded themselves that I was gradually going mad and actually endeavoured to induce me to enter a sanatorium where a certain Doctor Jung (the Swiss Tweedledum who is not to be confused with the Viennese Twiddledee, Dr. Freud) amuses himself at the expense (in every sense of the word) of ladies and gentlemen who are troubled with bees in their bonnets.I mention all these views not to speak about myself or my critics but to show you how conflicting they all are. The truth probably is that I am a quite commonplace person undeserving of so much imaginative painting.

0 Comments:

Publicar un comentario

<< Home